In The News

State commission wants to roll back a key part of post-Surfside condo safety law. Lawmakers are not so sure

WLRN-TV & WJCT-FM (First Coast Connect)

A new report issued by the Florida Building Commission calls into question a key part of a major law passed last year in response to the collapse of the Champlain Towers South building in Surfside, which left 98 dead.

At the core of the new bill was the creation of a two-tiered schedule of structural inspections for buildings across the state — with a stricter cadence for those located near the coast.

But the commission, which includes developers and contractors, claims that differentiating between how often coastal properties and inland properties need to be inspected for structural integrity has little basis in the real world. It’s a finding some architects and lawmakers flatly refute.

Instead, the commission recommends removing the distinction between coastal and inland properties in the law, and is requesting the legislature to bring all buildings under the less timely schedule requirements created for those located away from the coast.

The Florida Building Commission also recommended in the report that it be given authority to tweak the standards for inspections on its own, without having to go back through the Florida legislature and lawmakers.

Preliminary University of Florida research funded by the commission “suggests that there may not be an appreciable difference in the levels of degradation observed between coastal and inland structures, and that it may not warrant the additional administrative and economic burdens of treating them differently,” reads the report.

The idea of treating coastal and inland buildings differently has been at the forefront of the conversation ever since the collapse of the beachfront property in 2021.

The law that passed required all Florida condo buildings that are three stories or higher located within three miles of the coastline to conduct a ”milestone inspection” on the 25th year after construction, and every 10 years after that. Similar condos located farther from the coast would have to do the inspections on the 30th year after construction, and every 10 years afterwards.

Underlying the idea was an assumption that coastal buildings are exposed to conditions that make them more likely to degrade quickly.

But the report found otherwise, even as some of its findings seem contradictory — while a key aspect of the data used has been called into question.

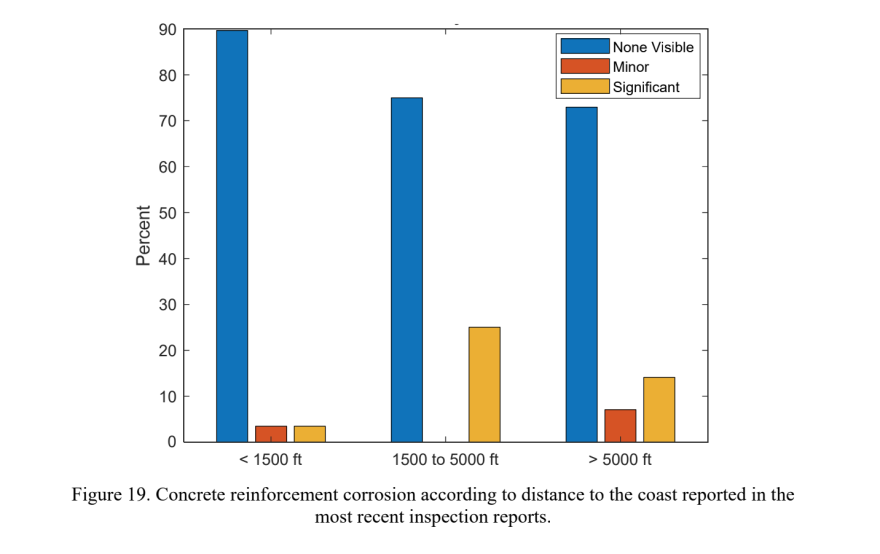

For its research, the commission analyzed more than 300 inspection records for 267 buildings throughout Miami-Dade and Broward counties, where 40-year inspections are already required. Buildings in coastal cities like Miami, Fort Lauderdale, Pompano Beach and Miami Beach were inspected, along with inland cities like Hialeah.

On the one hand, the report found that “there is a slight trend toward a higher percentage of buildings requiring repair the closer they are to the coast.”

And on the other hand, the commission found that buildings located further inland actually exhibited more issues with concrete reinforcement corrosion.

“This finding is more likely the result of the difficulty in detecting corrosion in embedded reinforcement with visual inspection techniques rather than a true measure of the presence of corrosion,” clarified the report.

Taken together, the report concludes that “there is no observable trend in the reported general concrete condition with proximity to the coast.” Instead, the commission recommends that all condo buildings be held to the same standard: having the first “milestone inspection” at 30 years after construction, regardless of where it is located.

If the state does not change the law and insists on differentiating between coastal and inland properties, the commission asks for lawmakers to clarify what it considers a “coastline” — that is, what is the point from which the three mile distance that outlines the coastal zone is measured.

For its analysis, the commission used something called the Florida Coastal Construction Control Line, a standard set by the Department of Environmental Protection. It recommends that if the state wants to continue differentiating, that it might simply use this line.

‘Statistics can lie’

But using this line for the analysis or for setting the definition of a coastline presents its own issues.

In South Florida, for example, this line runs along barrier island towns like Miami Beach and Palm Beach. That means the City of Miami, for example, might not be considered a coastal city, since it’s several miles west of the coastal line.

That might have skewed the data and statistics the commission gleaned from the research, said Thorn Grafton, a Miami-based architect who has worked on coastal construction projects. “Statistics can lie,” said Grafton.

Grafton called into question the recommendation to stop differentiating between coastal and inland areas, saying they run contrary to “common sense.”

“Anyone who has been fixing older buildings in South Florida knows that older buildings near the coast get affected by salt air,” said Grafton. “Typically we see the south and east side of buildings have a little bit more spalling — concrete cracking — than other sides, just because of the wind and salt that they get.”

Areas along the Coastal Construction Line are already subjected to different, higher standards in building codes partly for this reason. Members of the Florida Building Commission, who are appointed by the Governor, might not want to see different standards creep further inland, suggested Grafton. “I can sense a reluctance to deal with buildings in a different way just based on a line, one way or another,” he said.

READ MORE: State Sen. Pizzo On Surfside Tragedy, Rabbi Lipskar On Finding Hope, And A Key West Cruise Update

Commission members told WLRN they have been instructed by the DeSantis administration not to speak to reporters. “You know how things are right now in this state,” quipped one member.

Nonetheless, some members shared with WLRN that they felt it would be better to wait for the final results of a federal investigation by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, or NIST, into the Surfside condo collapse before they felt comfortable treating coastal properties differently than inland properties.

The final results of the investigation could take several years to be completed and released, NIST previously told WLRN. A full report NIST issued about the attacks of 9/11 took six years to complete; a report on the devastation wrought by Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico in 2017 is still pending.

At a committee meeting in the Florida Senate last week, Jeff Kelly, the director of professions at the Florida Department of Business and Professional Regulation, presented some overarching findings of the report to lawmakers. The department oversees the Florida Building Commission and speaks on its behalf for the DeSantis administration.

“What they’re saying is they don’t see the data to justify that yet,” said Kelly, referring to treating coastal and inland areas differently.

Bipartisan reaction to the recommendations

Democratic State Senator Jason Pizzo fumed at the recommendation.

“You punted to see what NIST comes back with,” said Pizzo. “You’re not drawing a conclusion. A five year-old could tell you that the corrosive elements of saltwater and high water table on concrete with rebar is far more aggressive, it should be aged in dog years. You punted.”

Republican State Senators Jason Brodeur and Jennifer Bradley appeared to agree with Pizzo.

“I don’t think I need a report to know that salt corrodes metal unless the laws of physics are different in different parts of the state. And so unless and until there’s some sanity on this, I’ll probably be down on some of these things,” said Brodeur.

Sen. Bradley added that experts consulted by Florida lawmakers had been “pretty clear” that coastal conditions “suggest that those buildings and their structural integrity would degrade faster and cause more of a concern, if your concern is life safety.”

Lawmakers also wondered out loud if there are enough inspectors in the state needed to perform all the inspections that are required by the new law, and if they might need to shift timetables in the future. The DBPR told lawmakers that there are only 600 qualified structural inspectors in the state, while there are over a million condo units across the state, but that it could not confidently say if the limited number of inspectors might create a backlog.

The first inspections required by the new law are required by December 31, 2024.

In the report, the commission noted that there are already systemic delays in completing the 40-year inspections that are already required in Miami-Dade and Broward. About 13 percent of those inspections happen five years after they are due, found the analysis.

“What we’ve given you is just not feasible. What we’ve handed down to our condo associations is just not possible. It’s just not possible,” said Pizzo, addressing the DeSantis administration.

The legislature would have to pass a new bill to put the Florida Building Commission’s recommendation into action, but it’s unclear if there’s the will to reverse such a core section of the law that they passed last year.